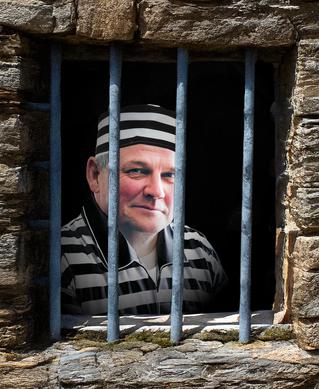

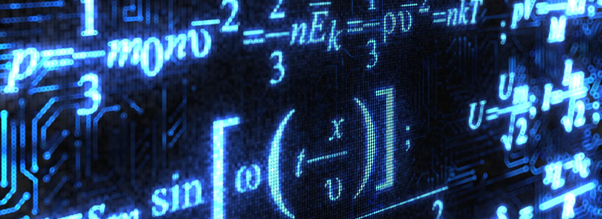

As Mr Bennett has now completed his first year as headteacher at Hitchin Boys’, we thought it would be the perfect time to find out a little bit more about the man behind the role, so a small group of Journalism Club students in KS3 and 4 sat with the head and asked him about life before Hitchin Boys’.

Sitting down in an interview room filled with relics of the school’s history - including whole school photos cfrom the past 100 years, as well as face paint boxes that Mr Bennett acquired to aid him in the daunting task of transforming faces at the school Christmas fair - we took a dive into Mr Bennett’s character in a wide-ranging interview where we discussed his links to current celebrities Alex Gray (AKA Gladiator Apollo) and ex-England rugby union captain Jamie George (who was coincidentally born in Hertfordshire) to the lighter side of his personality; from his favourite subjects to what he would do on a desert island.

Childhood

As a school child of the 1970s and 1980s, Mr Bennett had many interests such as maths, science and PE, so it is no surprise that he later became a maths and PE teacher, perhaps influenced by the time he worked in a school where his mum was a nurse. During the school holidays, Mr Bennett ran holiday camps for children, so his quality time with his family was at the weekend. His ideal weekend involved playing sports with his much loved brothers and sister and going to church on Sundays, where his father worked as a vicar.

Sporting Journey

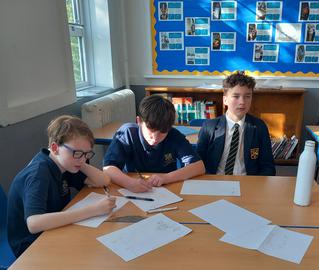

Mr Bennett’s sporting journey has led him across the country in many different roles, from recreational rugby and cricket into the international university game to senior club rugby. During his career, Mr Bennett has had a passion for coaching; this passion became real when he was selected to take a role in the coaching of the England U16 rugby team, where he crossed paths with now-celebrities Jamie George and Alex Gray. Mr Bennett said that both the small and the big opportunities he experienced throughout his career were ‘crucial’ in enabling him to be the headteacher he is today.

Mr Bennett's time in the sporting world has been a long one and there have been some stand-out moments that have taught him important lessons. During a Kent County U18 Rugby game, there was a point when Mr Bennett made an error which ultimately resulted in the loss of the game. However, his teammates forgave him, as captain, because he took accountability for his mistake but it’s a mistake he’s never forgotten.

Nicknames, books and desert islands

Moving on to the less serious side of Mr Bennett’s life, it’s probably worth mentioning that his favourite animal is a moose. His daughter’s nickname was Goose, so together they were known as the Goose and the Moose! Growing up, Mr Bennett's favourite book was Danny the Champion of the World by Roald Dahl and he shared with us the memory of him running out of primary school in excitement because he had read 10 books, only for his mother to reply: “No Tim, you’ve just read Danny the Champion of the World 10 times!” For Mr Bennett, revisiting the book as an adult, with his son, has been an enjoyable experience, as his son has embraced the book too. In fact, Mr Bennett enjoys reading so much that if he were to be marooned on a deserted island, as well as a rugby ball (obviously!) and an Alexa, he would take a complete series of Bernard Cornwell books!

Head’s high hopes

The role of a headteacher is extremely challenging, so why did he choose this particular role? Well, Mr Bennett believes in all students becoming anything they want to be. Being part of the Hitchin Boys’ community links with his values, so he wants to make every student’s school experience as good as it can be. Most importantly, Mr Bennett hopes that students will have such a great experience that when they leave school, they will say, ‘I loved my time at school!’ We think that’s a good mantra to live by and one that summarises not only the school's values, but also Mr Bennett's personal character.

By Finn, Leon, Jack and Robbie

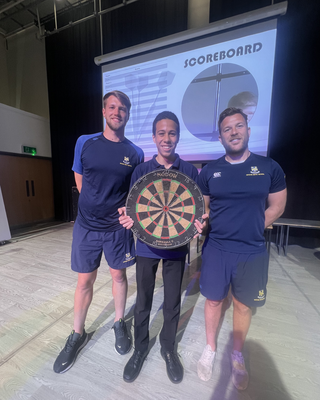

Mr Bennett (left) in his coaching days